Make friends with the wind

The Portuguese call the great swirl of wind in the north and south Atlantic the Volta do Mar. It gave them a vast maritime empire, and it still gives yachtspeople a route to an excellent Azorean bar

We were in Horta, the capital of the Azorean island of Faial. It was summer and at night we heard the sound of jolly partying. Faial is a long way from being the busiest island in the Azores: it has about 15,000 of the archipelago’s 243,000 people. But it is probably the most fun. That’s because the marina in Horta is packed gunwale to gunwale with sailing boats. They are not small, but they are not large either – most are 30 to 40 feet long, with space for a handful of crew. It was the crews, with some locals and tourists, who were doing the partying

What the boats have in common is that they definitely don’t look brand new. The level of batteredness varies, but none comes close to pristine. It would be surprising if they did, having sailed thousands of miles in the open Atlantic to get here. The Azores are a service and rest area for yachtspeople crossing the Atlantic. Indeed if you want a break mid-Atlantic, you have no other choice.

There is a tradition at the marina of painting a small mural - maybe three feet by two – on the harbour wall. Every crew that comes here is expected to paint one, and there are thousands – a cacophony of colour. Comparing photos taken on my three visits, I would say they last about 10 years before they are painted over. Some are beautiful; some are very simple; some are both. But they each tell a story – the name of the boat, the date, usually the crew and where they come from, and other clues: ‘Atlantic tour’, ‘Around the world’, ‘Hamburg to Caribbean’. Flags and registration reflect the mix – mainly European, but we also saw Mexican, Australian, South African … Here is one from Ukraine, with the volcano Pico behind:

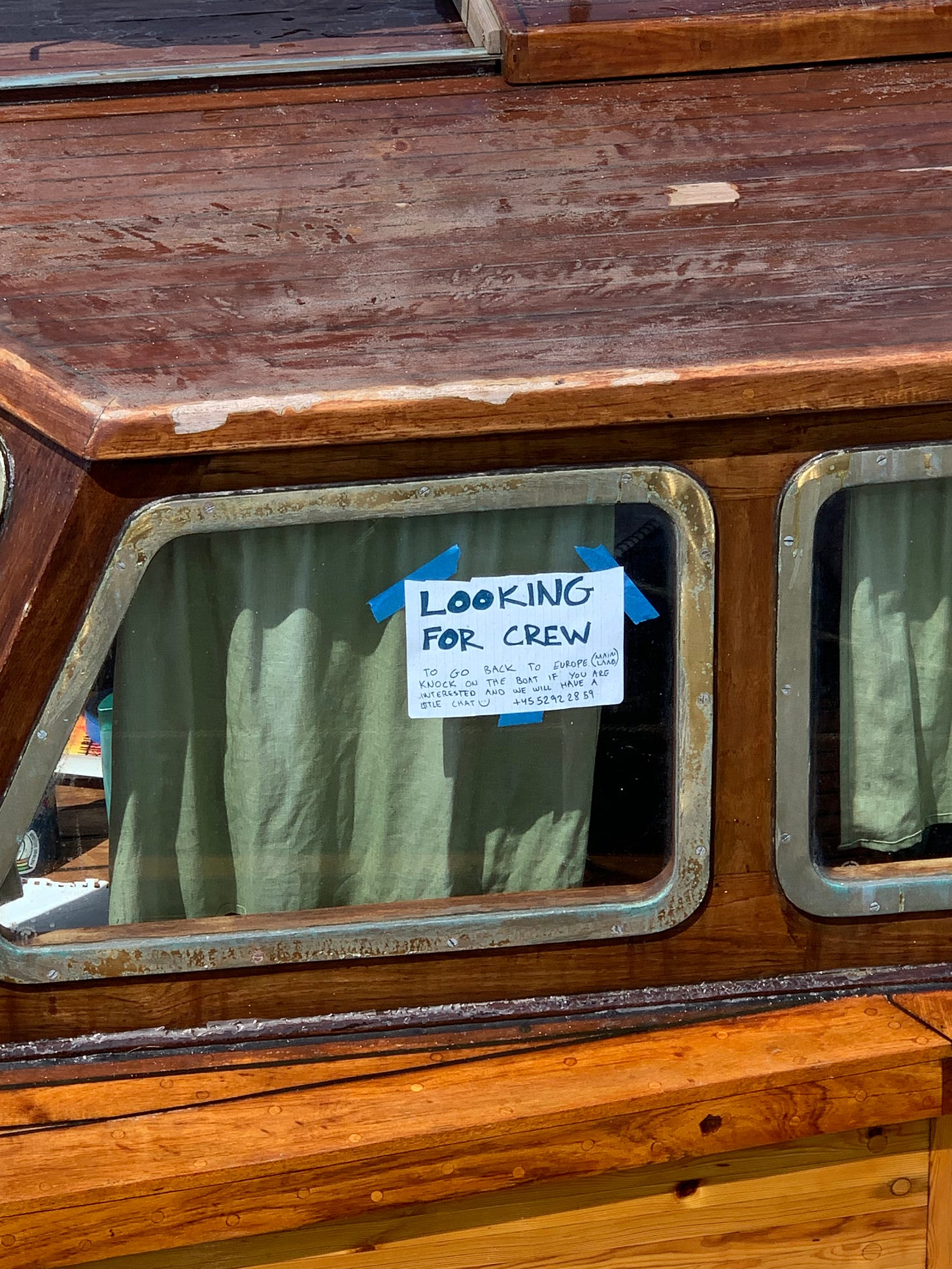

Some of the boats have notices on them. The lovely yacht Ocean Fregatta in my first photo has one headed ‘Looking for crew – To go back to Europe, knock on the boat if you are interested.’ The phone number identifies the skipper as Danish.

The real crew exchange is however in Peter’s Café Sport, opposite the marina. It gets called the most famous sailors’ bar in the world, and has a mix of tourists like us and people off the boats. You can tell the difference because the tourists look like tourists; the sailors look like walnuts.

It’s a noisy, happy, multilingual place. It feels like it ought to be a tourist trap, but it isn’t, not really. The bar is lined with more notices: ‘Wanted crew for Horta to France’, ‘Young guy looking for a first sailing experience’, ‘In desperate need of crew for crossing to Ireland, Shetland and Norway’. Pennants, signed, hang from the ceiling and the walls.

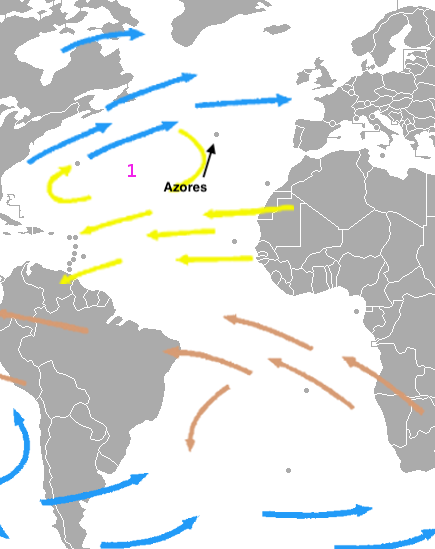

Looking at a map of the Atlantic, it is not surprising that so many yachts choose to take a break here. You can moor in the massive marina, buy what you need for your boat, and rest and drink Peter’s gin & tonic. But there is a more specific reason why the Azores have long been a destination for people heading by sail to Europe. This map of prevailing winds is a clue:

Source: KVDP

What the Portuguese call the Volta do Mar – the Turn of the Sea – is the great circle of wind that swoops over the Atlantic. Or rather circles: there are two, one above the Equator, one below.

The Portuguese were able to build the first European maritime empire largely because they understood the wind flows. In the fifteenth century, Portugal was an impoverished country always under pressure from its giant Castilian neighbour. What the Portuguese did have though was coastline, lots of it, and with that a deep knowledge of how to handle the sea. They used their skill at first for fishing then for exploration. Prince Henry - called the Navigator - was the fourth son of the Portuguese king and first cousin of Henry V of England. He decided Portugal must expand around the world, partly to bring wealth, partly to outflank the Muslims, who dominated so much trade. He assembled local fishermen, Arab specialists and others to design a new sort of ship called a caravel, and to gather the skills that would send his sailors where no European had ever been.

He wanted in particular to get to India, where he knew there was great wealth. He was most keen to avoid the Red Sea route, which relied on Muslim traders. Maybe there was a river right through Africa – his caravels could investigate? But the other option – the right one – was to go round the bottom of Africa and up the other side. And this is where his sailors discovered the Volta do Mar. It was impossible to cling to the coast of Africa and turn left at the bottom: the winds blew them out to sea. Instead they found that if they headed way out south and west they could pick up the winds that headed east, past the Cape of Good Hope. It had other advantages. In 1500 they bumped into Brazil while doing the great loop, and landed on pretty much every island in the Atlantic, occupying several of them. That is why São Tomé and Principe, Cape Verde and Madeira all became Portuguese. And why the British territory of Tristan da Cunha has its name: it was spotted and named by the explorer Tristão da Cunha in 1506.

But the wind goes in a great circle in the North Atlantic too, swirling the other way. Ships coming back from the south had to swing way to the west to pick up the winds that would sweep them back to Lisbon.

There are wind circles like this all around the world, which the early explorers – many Portuguese - discovered by trial and error. It must have been terrifying. Few sailors in the fourteenth century had been out of sight of land; in the fifteenth they were spending weeks at a time in the middle of the sea. They even, the Portuguese say, went to North America 20 years before Columbus: adventurers backed by the king went to Terra do Bacalhau - Land of the Cod – in 1472. A much better name than Newfoundland, as the unimaginative British called it.

After Brazil became Portugal’s most important colony, returning galleons would guide themselves into the best wind flows. That brought them close to the Azores, where they could rest, stock up and, at times, gather themselves into convoys to ward off marauding pirates.

Yachtsfolk navigating the Atlantic today are I hope not terrified, but they must certainly understand the winds. If you want to go west from Europe to America, sail south first and you will be carried west. But if you want to go the other way, go north then east; sweeping close to the Azores.

The prevailing winds are given nice support by the currents – the Gulf Stream sweeps across from the Caribbean to Europe past the Azores. As with the winds, currents flow the other way further south. It is all very handy – if you know what is happening. And it has put the archipelago at the centre of the Atlantic sailor’s world for centuries.

Here are some more stories about the Azores:

Young earth - a volcano rises out of the sea

Moving continents - why Roosevelt decided the Azores should be in America

Fascinating stuff!

Lovely breezy prose. I really get your love of the Azores and it’s international ‘bring and buy sale’ for captains and cabin boys.