Einstein was right

An experiment on the island of Principe catapulted him into the international limelight

The island of Principe is the little sister of São Tomé in the tiny country of São Tomé and Principe, which sits on the Equator off the west coast of Africa. I wrote about where it is here. It is seriously beautiful.

We flew there on a propeller-driven plane which, judging by the safety signs, had spent its earlier life somewhere Cyrillic, possibly Russia. It must have had a shock when it moved to the Equator, but it took us safely to the tiny airport.

Principe is much smaller than São Tomé, with a population of only about 7,000, and it has been moulded into something of a tourist paradise. It was made a UNESCO Biosphere Reserve in 2012, which means it is a ‘learning place for sustainable development’. We saw a giant green turtle burying her eggs on a beach at midnight, watched over by a concerned Brazilian biologist. We went for a walk in the forest and discovered why it is called a rain forest (I’ve never been so wet). And we visited the place that made Albert Einstein a star.

Roça Sundy is now a nice hotel, one of several that were restored by Mark Shuttleworth, a South African software whizz. In 2002 he became the second space tourist, paying $20 million for a trip to the International Space Station. More relevant here, he owns three of the handful of hotels on Principe, has done up the airport, says he has put more than $100m into the island, and is keen – along with the island’s president – to see if it can become a model for eco-tourism.

Like most of the posh hotels on São Tomé and Principe, Roça Sundy used to be one of the houses on a cocoa plantation (roça means plantation in Portuguese). These had a terrible reputation for working conditions 100 years ago, as I wrote here, and it stopped producing soon after the country became independent from Portugal in the 1970s. It opened as a hotel in 2017.

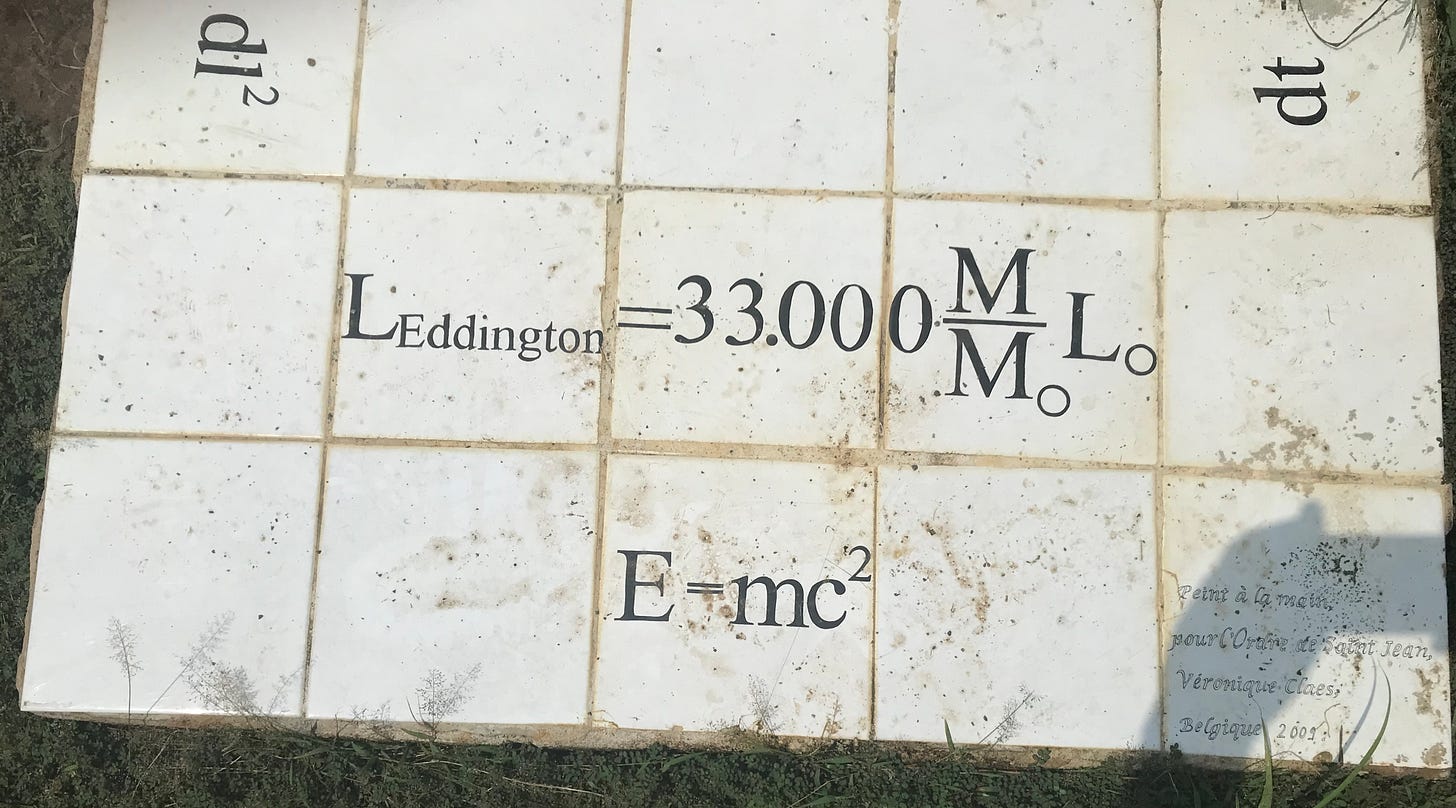

But it was already celebrated for quite a different reason. Just by the main building is a cluster of plaques. A square of tiles on the ground is covered in mathematical formulae, one of which even I recognised:

Another was way beyond me, though I did wonder why the word ‘Eddington’ was built into a formula.

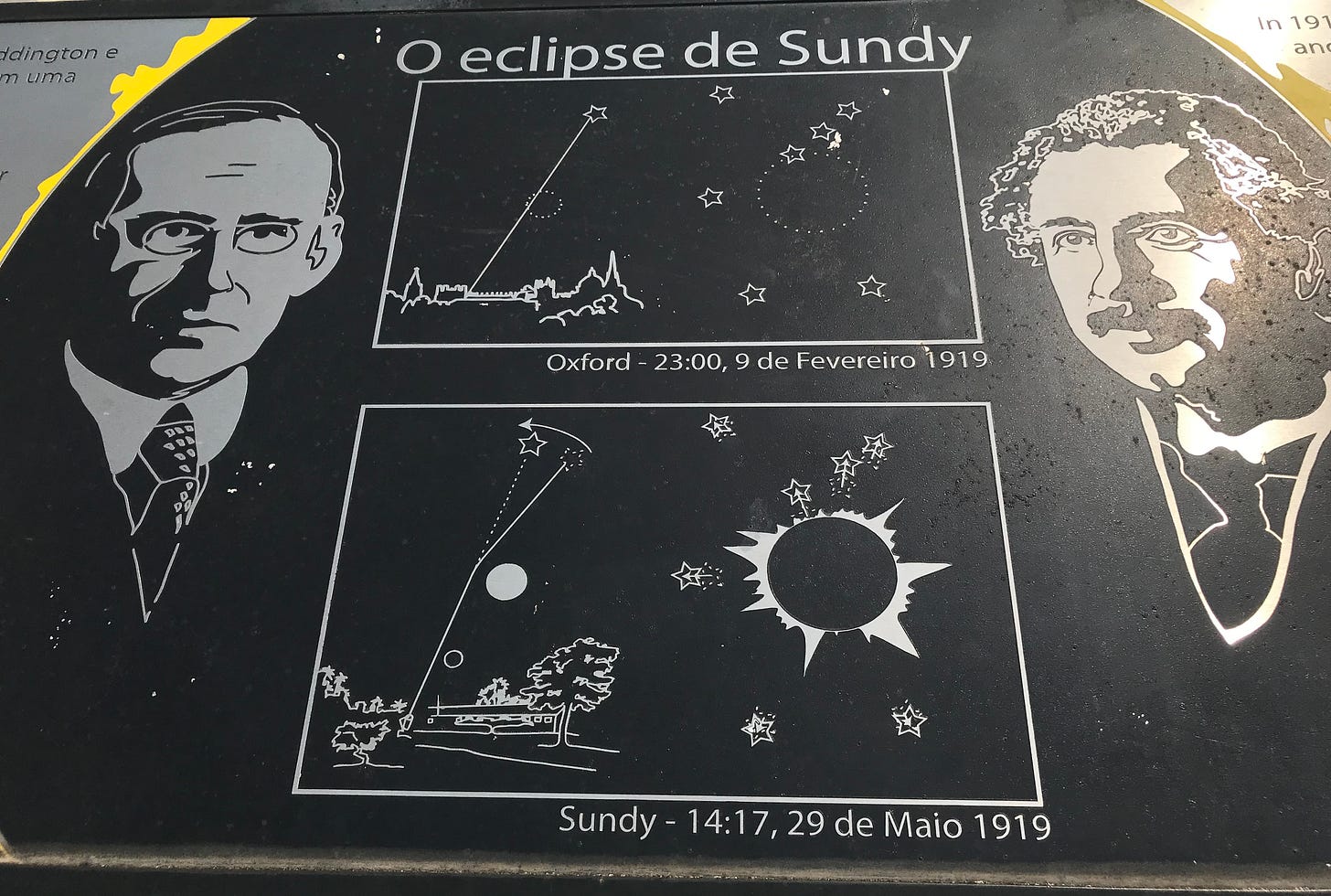

A separate panel explained. Here is Arthur Eddington, alongside a more familiar face: that of Albert Einstein. The heading is ‘The eclipse of Sundy’, and there are stylised stars and what looks like an explosion. This was the location of one of the most important experiments ever: the one that established Einstein’s theory of relativity was right, and turned him from respected physicist to superstar.

It was all to do with how far light bends when it goes near a massive object, like the sun. Newtonian physics had already been used to show that this would happen and by how much. But Einstein reckoned, using his theory of relativity, it would actually be twice as much. Eddington, professor of astronomy at Cambridge, was one of the few people who understood the theory of relativity, and he knew that the best way checking who was right was by watching the sky during a full solar eclipse. That was when you could see the sun, but also the stars.

Scientists had wanted to test Einstein’s calculations from 1911, when he first came up with a number. An unfortunate German-American expedition had tried to do this experiment in the Crimea in August 1914. Bad timing: the Germans ended up as prisoners.

But it was lucky for Einstein because he realised he had got his numbers wrong, and revised them in 1915. The First World War made great scientific journeys implausible, and Eddington’s ambitions were very nearly thwarted by his conscription to the front. In 1918 the Astronomer Royal, Frank Watson Dyson, managed to get him off by proposing that he undertake an expedition to observe the next year’s eclipse.

The eclipse was visible from equatorial regions on both sides of the Atlantic; Eddington sent one team to Sobral in Brazil, and himself went to Príncipe with Edwin Cottingham, a clockmaker who set up the instruments. They needed to compare the positions of stars close to the Sun during the eclipse with their night-time positions three months earlier (hence the ‘Oxford’ graphic on the board).

The eclipse was due to take place in the early afternoon of 29th May, at 2 pm, but that morning there was a storm with heavy rain. ‘The rain stopped about noon and about 1.30 ... we began to get a glimpse of the sun,’ he wrote. ‘We had to carry out our photographs in faith. I did not see the eclipse, being too busy changing plates ... We took sixteen photographs. The last few photographs show a few images which I hope will give us what we need ...’ They did – and they agreed with Einstein’s sums.

When the scientists announced their results the newspapers went mad, in a 1919 sort of way. ‘Light all skew in the heavens – Men of Science More or Less Agog Over Results of Eclipse Observations,’ the New York Times shouted. Inevitably not all Men of Science were Agog, and argument about the findings rolled on for years (it took the arrival of radio-astronomy to provide absolute proof that Einstein was right). But the president of the Royal Society in London was convinced. This was ‘one of the most momentous, if not the most momentous, pronouncements of human thought’. An article in the London Times bravely tried to explain relativity: ‘space may acquire a twist or warp in certain circumstances, as for instance under influence of gravitation’. Most of us these days are used to hearing such things, even if we don’t understand them. A hundred years ago, they must have been a source of utter astonishment.

Einstein was already well respected in Germany, but this finding catapulted him to international fame.

Eddington was no slouch either: he even had his own ‘luminosity’ - that was the ‘Eddington’ in the formula. He was also clearly a jolly soul, and wrote a little poem that ended: ‘One thing is certain and the rest debate, Light rays, when near the Sun, do not go straight’.

Another really interesting piece